A Short History of the King James Version of the Bible

The King James version of the Bible is often considered the gold standard for modern translations, but few of us are familiar with its history, mandate, publication and early printing. This article provides a brief glimpse in the hope that we will understand it and its historical context a little better.

The Bibles in Use at the Time

Any history of the English versions of the Bible has to begin with the work of William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale. Tyndale translated the New Testament and significant portions of the Old Testament from Greek and Hebrew into the English language in the 1520’s. In so doing he raised the wrath of the Catholic Church, and he was ultimately strangled and burned at the stake. His translation was of sufficient quality that significant portions of his translation were used in subsequent English translations. Myles Coverdale is credited with producing the first complete translation of the Bible into the English language. This was published in the 1530’s. Like Tyndale’s work, his translation and wording was used extensively in subsequent translations. The contribution of both Tyndale and Coverdale to both translation and to the Reformation movement in the English-speaking world cannot be underestimated.

In the early 1600’s there were three Bibles used in English Churches. The highly regarded Great Bible had been developed by Myles Coverdale at the request of Thomas Cramer, Archbishop of Canterbury, under the reign of Henry VIII in 1535. It was large – over 15 inches high, (hence its name) – and copies were distributed to all churches where they were chained to the pulpit. Its New Testament depended largely on Tyndale’s earlier translation. The Great Bible was the first “Authorized” English Bible.

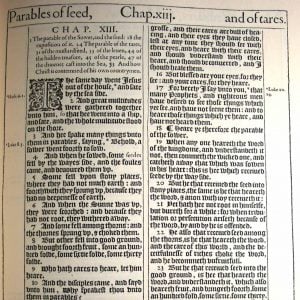

Part of Matthew 13 in a 1611 print of the King James Bible

The second Bible of significance was the Geneva Bible. Published in 1560 it was the work of Protestant English scholars who had fled England to Switzerland during the reign of Catholic Queen Mary I. William Whittingham supervised the translation, working with other scholars including Coverdale, Goodman, Gilby, Sampson and Cole. The Geneva Bible was the first mechanically printed, mass-produced Bible made available to the public directly. It was also the first Bible to introduce numbered verses, making the Bible easy to study. To enhance its study potential, it contained copious annotations. These notes had been written by Calvinists and Puritans and were contentious to both the monarchy and the bishops of the high Church of England. However, it became the most widely popular Bible at the time and remained so for some time even after the publication of the King James Bible. It was the Bible familiar to Shakespeare and was one of the Bibles taken to America by the Plymouth Pilgrims. It also depended largely on Tyndale for the New Testament translation.

In 1568 a revision of the Great Bible, known as the Bishops’ Bible, was produced, mainly as a reaction to the Geneva Bible. It was not mass-produced as it was intended as a pulpit Bible, but it was not as popular as the Great Bible.

The Politics

King James VI of Scotland succeeded Queen Elizabeth I of England to become James I of England. He was the son of the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots. It was a time of unrest between the Scottish Protestant Parliament and the Catholic Monarchy. His mother abdicated while he was quite young. Thus, when James 1 became king, Scotland was essentially ruled by the Protestant regents until he became 18. As a consequence, he was brought up as a Protestant. One of his aims was to unite the Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. He had strong views about the monarchy’s divine right to rule. In England, he tolerated Catholics, provided they swore allegiance to the throne.

In Scotland, the ruling Protestants were fairly intolerant of Catholics, and Scotland was the scene of some of the worst persecution of Catholics by Protestants. England had separated from the Holy Roman Empire under King Henry VIII, not as result of reform, but for political expediency. The Church of England was the state church and, to a large extent, was very similar to the Roman Catholic Church, except that the King had replaced the Pope. Within the Church of England were two opposing factions – the Papists, who wanted the Church to return to the Roman Catholic Church – and the Puritans who wanted to purge the church of any Roman Catholic influence at all. Religious persecution was fairly common. Roman Catholics were allowed to practise, provided they swore allegiance to the King. Puritans were somewhat tolerated, provided they were relatively quiet. Of course, some of the Puritan leaders did not keep quiet and they, together with their congregations, were known as “Dissenters.”

The tensions between the religious factions is highlighted by two notable events that occurred during King James’ reign. The Papists attempted to blow up the English Parliament in 1605, an event associated with the name Guy Fawkes, who was caught guarding the explosives under Parliament House. Secondly, the Pilgrim Fathers, who were essentially dissident Puritans, left England (circa 1607) for Holland and ultimately America.

Culture and Literature

During the reign of James I, literature flourished and the English language came into its own as a literary force. William Shakespeare, John Donne, Ben Jonson and Sir Francis Bacon were all active during this period and all made a significant contribution to the literary culture of the English language. It is notable that the King James version of the Bible was translated during a period when English language was gaining respect as a language for literature. Even today unchurched literary experts acclaim the value of the Bible as literature.

The Mandate

In this setting James convened the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 for a discussion between the King, and representatives of the Church of England, including the Puritans. The conference was a response to a request for reforms from the Puritans to remove Catholic terminology and practices from the Church. Initially the conference accepted many of the Puritans’ requests, but unfortunately John Whitgift, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died and was replaced by Richard Bancroft, who was anti-Puritan. Ultimately, the main concession won by the Puritans was that man should know God’s Word without intermediaries.

This led to James I calling for a new translation of the Bible, authorized to be read in churches. The mandate for the new Bible translation included:

- Instructions intended to ensure that the new version would conform to the ecclesiology and reflect the episcopal structure of the Church of England and its belief in an ordained clergy[i]. Certain Greek and Hebrew Words were to be translated so that they reflected Church of England practice.

- The new translation was not to have marginal notes. This had been an issue with the Geneva Bible as it had extensive notes that were viewed with disfavour by both the Papists and the monarchy.

- It must be written in a language that is familiar to the readers and listeners. One effect of this was that anglicized names were used wherever possible.

The Translation Process

Fifty-four translators were called to make up the translation workforce. Eventually forty-seven translators were involved as some were unable to participate for various reasons. All except one were Church of England clergy and included scholars with both High Church of England and Puritan sympathies. (The names of the translators, the committees they sat on and the sections they translated have all been recorded together with their collected working papers and marked up corrections to one of the Bishops’ Bibles.) They worked under the supervision of Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury. There were two committees in each of Oxford University, Cambridge University (church operated universities), and Westminster University. They worked separately and cross-checked each other. They translated from the original languages and compared their work with previous English translations (i.e. Tyndale and Coverdale). The translation was essentially completed by 1608. In 1609-1610 the work was reviewed by a review committee. Archbishop Bancroft had the final say, making fourteen final changes after the committee stage. One of these was the term “bishoprick” in Acts 1:20.

Publishing and Printing

The initial printing was run in 1611 and sold for 10 shillings loose-leaf or 12 shillings bound. Two editions were printed in 1611 known as the “He” (1st Ed) and “She” (2nd Ed) Bibles based on their rendering of Ruth 3:15. The original printers fell into serious debt and printing was assigned to two rival printing companies, who engaged in rather spurious business practices. There was a rather embarrassing row between them.

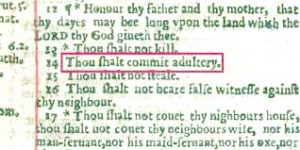

Mis-printed KJV

Spelling in the English language had not been standardized when the King James version of the Bible was first printed and printers made their own revisions to spelling, punctuation and grammar where they thought it was needed to reflect current usage. Further, proof reading was not as thorough as it should have been. One notorious printing omitted the word “not” from the commandment, “Thou shalt not commit adultery.” [ii] The printers printed 1000 copies with this error and were fined 300 pounds for their mistake. Although they were supposed to have been recalled and destroyed, some are still in existence today (At the time of writing this article, one is currently on offer for over $100,000). By the mid 1700’s the variations in the King James Version prints had reached the stage where it was embarrassing and could not be ignored. This led to a revision and standardization.

The 1769 Revision

In the 1760’s the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge undertook to standardize the text, reverting as much as possible to the original 1611 version but at the same time adding corrections and improvements of their own, mainly under the direction of Benjamin Blayney. The 1769 version that was produced from this effort incorporated these changes and differs from the 1611 text with about 20,000 spelling and punctuation changes and 400 wording changes. Most of the spelling revisions were due to the issues like the use of “u” and “v”.

Word change examples:

TOWARDS has been changed to TOWARD 14 times.

BURNT has been changed to BURNED 31 times.

AMONGST has been changed to AMONG 36 times.

LIFT has been changed to LIFTED 51 times.

YOU has been changed to YE 82 times.

In Genesis 22:7 AND WOOD was changed to AND THE WOOD.

In Leviticus 11:3 CHEWETH CUD was changed to CHEWETH THE CUD.

In Romans 6:12 REIGN THEREFORE was changed to THEREFORE REIGN.

To give you some idea of how the 1611 and 1769 versions compare for reading, here are parallel quotes from 1 Cor 13, 1-3.

[1611] 1. Though I speake with the tongues of men & of Angels, and haue not charity, I am become as sounding brasse or a tinkling cymbal. 2 And though I haue the gift of prophesie, and vnderstand all mysteries and all knowledge: and though I haue all faith, so that I could remooue mountaines, and haue no charitie, I am nothing. 3 And though I bestowe all my goods to feede the poore, and though I giue my body to bee burned, and haue not charitie, it profiteth me nothing.

[1769] 1. Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. 2 And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing. 3 And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

In this passage, there are 11 changes of spelling, 16 changes of typesetting, three changes of punctuation and one variation in translation.

The King James Version in use today is largely the same as the 1769 Blayney revision, in spite of the fact that the modern preface often states the 1611 publication date.

Authorization

The original King James Version was published with the annotation, “Appointed to be read in Churches” on the title page. This annotation was most likely approved by the Privy Council, but records of their actions in the first two decades of the 1600’s were lost in a fire in 1619. The term “Authorized” was used on the title page of the King James Bible sometime in the early 1800’s. There is evidence that “Authorized” was used in the description of this version in other literature in the late 1700’s. Significantly “Appointed” and “Authorized” were terms used by the government and the Bishop’s council to indicate that the version was the one that must be used in the Church of England. The King James Bible was the third Bible to be “Appointed to be read in Churches.” The earlier ones being the Great Bible and the Bishop’s Bible.

Conclusion

Like all translations, even modern ones, the King James Version is a product of the circumstances of its time. It was written at a time when Church and State were not separated. However in spite of its mandate and history of publication, it is still a clear record of God’s dealings with man.

References

[i] Daniell, David (2003). The Bible in English: its history and influence. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

[ii] Herbert, A. S. (1968). Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible, 1525-1961, Etc. British and Foreign Bible Society.

Source Material

Much of the background material for this article came from Wikepedia. Words used in the searches included; Tyndale, Coverdale, King James Version, Great Bible, Bishops Bible, Kings James VI and I.

|

If this post piqued your interest, you may be interested in one of the following books: How We Got Our Bible, by Timothy Paul Jones is a broad overview, not an in-depth history. Filled with dramatic stories of how people risked their lives to bring us the Bible in our language and highly-visual charts and illustrations, this Bible History handbook will take you from the earliest clay tablets and papyrus copies to the first bound Bible and the various Bible translations that we use today!

Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing Cultural Blinders to Better Understand the Bible, by E Randolph Richards,delves into the culture of Bible times to allow us to see what the original writers had in mind. For instance, we tend to think of Jesus being born in a detached stable/barn. But the author suggests that it is more likely that Jesus was born in the stable part of a peasant home, with the stable being on a slightly lower level than the living area, complete with diagrams. Many more such fascinating details.

Alternately, you can check out The King James Version Debate: A Plea for Realism by D. A. Carson which is available in Kindle format as well as paperback. If you are familiar with any of these books, please feel free to leave feedback. |