Are Adventists Old-Covenant Christians? (Part 5)

In the previous post, we identified where Adventism fits in relation to covenant theology. The conclusion placed Adventism closest to the views espoused by the 2nd London Baptist Confession, a covenantal framework that falls under the tradition of the Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Baptists known as “Covenantalism.” The post concluded by sharing some points on how this identification is helpful for the church.

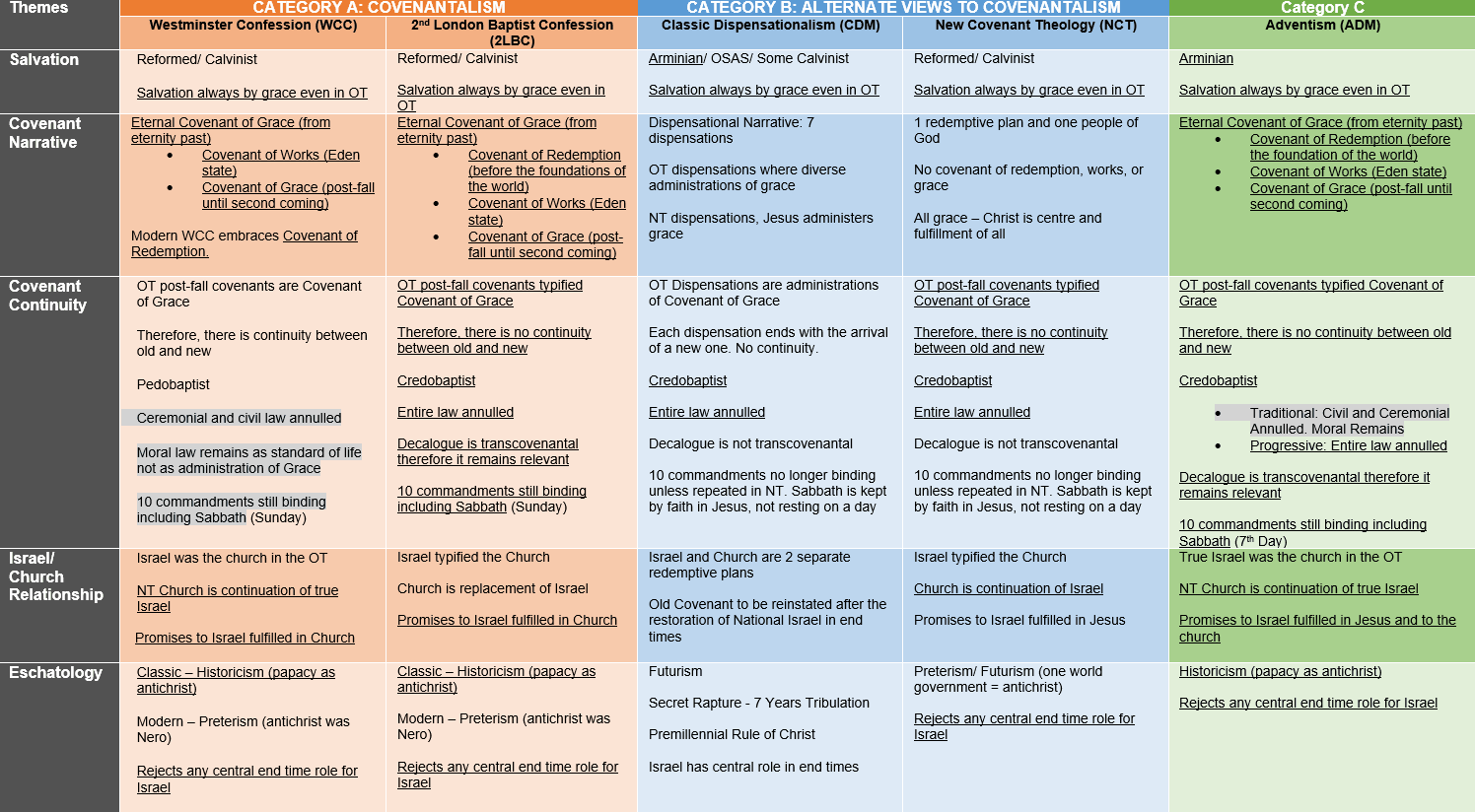

As we launch into the final posts of this series I will re-introduce some of the concepts mentioned before in order remind the reader of the important elements before moving forward. The first concept was introduced in the second installment of this series and identified the different types of covenant views that exist in Christianity. Covenantalism falls under Category A leaving the other two systems in Category B. The significance of this lies in the fact that the views under Category A all teach the perpetuity of the law, while the views under Category B reject it.

|

Category A |

Category B |

|

Covenantalism 1) Westminster Confession 2) 2nd London Baptist Confession (Embrace Perpetuity of Law and Sabbath) |

Alternate views to Covenantalism 1) Dispensationalism 2) New Covenant Theology (Reject Perpetuity of Law and Sabbath) |

Below I have also included the chart which summarized the last post. Make sure you open the chart in a new tab or new window to make it bigger. Then you can enlarge it further by clicking on the plus sign under your cursor.

In today’s post, the objective is to return to the start of our discussion on the narrative of Adventism and focus more on that which makes its narrative unique in the Christian world. Below is a visual of how that narrative was introduced in the first post. For a recap re-read the first post here.

In today’s post, the objective is to return to the start of our discussion on the narrative of Adventism and focus more on that which makes its narrative unique in the Christian world. Below is a visual of how that narrative was introduced in the first post. For a recap re-read the first post here.

BIG STORY

(God before creation)

↓

MIDDLE STORY

(Battle between good and evil/ Great Controversy)

↓

LITTLE STORY

(History of man/ Covenants)

In the first post, the question explored was “Why do Adventists seem to ignore covenant thought?” The above breakdown was given on how Adventists generally understand the story of Scriptures followed by the following chart.

|

Big Story – God |

Middle Story – Universe |

Little Story – Earth |

|

Who is God? What is he like? What are his attributes? What is his essence? (Arminianism) |

Why is there evil? Where did sin originate? Is God responsible for pain? Vindication of God’s character. (The Great Controversy) |

How did man fall into sin? How can we be saved? How does God relate to us? Where is our world headed? (History/ Covenants/ Prophecy) |

Because Adventists generally focus more on the Big and Middle stories we have tended to place less emphasis on the covenant progression in Scripture, which is part of the little story.1

In today’s post, I would like to briefly introduce Adventist thought within the covenant framework. It is my hope that in doing so Adventist theology will make a bit more sense to both our members and those whose theological traditions differ from our own.

Presuppositions Inherent In Adventism

The discussion begins with a brief overview of certain key presuppositions inherent in Adventism. Because our presuppositions impact how we read the Bible which in turn impacts our theology it is important to introduce these before moving into an exploration of our worldview. This overview is, once again brief in that it touches lightly on how to interpret the Bible – a hotly debated topic within the Adventist church.2 Nevertheless, the points mentioned here are basic and necessary as we move forward in our exploration.

Bible Alone As Authoritative

While Adventism adheres to all 5 of the principles of the Protestant Reformation it holds the Bible-Alone principle higher than the others, for without it we would have no concept of Faith Alone, Grace Alone, Christ Alone, or To His Glory Alone. Thus, Adventism seeks to base its entire worldview on that which is revealed in Scripture alone and aims to be faithful to its teachings alone.3 As a result of this approach, Adventism has inherited and developed other presuppositions which we will now explore below.

Character of God

The Bible alone is our rule of faith and practice and its central theme is a revelation of Gods character of love – a picture of who he is and what he is like. For Adventists, the narrative of Scripture cannot be properly understood with a wrong picture of God. Scripture is, without a doubt, full of stories and events that are sometimes difficult to interpret. But there can be no hope of discovering truth if we approach these with a wrong picture of God. For an Adventist, God’s character of love has interpretive priority over any scriptural theme. One way of understanding this is illustrated below:

|

↑ ↑ ↑ Mystery |

Big Story – God is love. Mysterious but Simple. No variables. |

Complexity ↓ ↓ ↓ |

|

Middle Story – Universe Not as mysterious but Complicated. Variables introduced. |

||

|

Little Story – Earth Least mysterious but very Complex. Endless variables. |

According to this chart, while the Big Story is the most mysterious theme in Scripture in that our mortal minds can hardly fathom its depth, Scripture nevertheless gives us an extremely simple description when it declares that “God is love.” This declaration is so simple and clear that it is presented without any variables. God is love. Pure and simple.

From there, we can see Scripture introducing us to a Middle Story which Adventists refer to as the Great Controversy. This story is more complicated than the Big story in that more variables are at play (Angelic free will decisions), though it’s not as mysterious. We have more information about it and our mortal minds can grasp it with more depth because this story deals with creation and the battle between good and evil in the universe.

The Little Story, on the other hand, is the least mysterious. It deals primarily with our world and as such, we can sink our teeth into it quite well. However, it is also the most complex for it interacts with endless variables (free will decisions of angels and men, ripple effects of those decisions from person to person, nation to nation, etc.). As a result, one cannot reinterpret the Big Story based on something that takes place in the Little Story. For example, God ordering the Israelites to slaughter the Canaanites is a complex Little Story event that can only be fully understood when a significant number of its variables are considered and thus cannot be used to redefine the simple, variable-free Big Story: “God is love.”

Since the character of God is the Big Story, Adventism gives his character interpretive priority over the events that transpire in the Middle and Little stories. As previously mentioned, this is one reason why, for Adventists, the covenants can never be understood to abrogate the law of God. If God’s law is an expression of his character of love we cannot use a Little Story (covenants) to do away with a feature of the Big Story (love), for such an act would be illogical. This is why Jesus said, “It is easier for heaven and earth to disappear (Little Story) than for the smallest point of God’s law to be overturned (Big Story)” (Luke 16:17). Thus, while a proper exploration of the covenants is still necessary in order to make sense of redemption history, God’s requirements of his people today, and the way in which the Big Story has interacted with the Little Story, most Adventists are content to never question the place of God’s law either in time or eternity so long as its in a right relationship to the gospel. Once again, this is one reason why many Adventists simply appear to overlook the covenantal progression of Scripture – a posture which I have argued against in this series. For them, so long as the law is in a proper relationship to grace they are content to put most of their emphasis on the character of God.

Sanctuary Narrative of Adventism

Adventism also approaches Scripture with the view that God is within time. While Adventism does not deny the eternality of God and holds that God exists outside of time, it does not attempt to define or explain this mystery on the basis of Scripture’s silence. Additionally, while Adventism is compatible with an exploration of the philosophical implications of a timeless deity, it does not use those implications to form a theology. Rather, Adventism approaches Scripture with a God-in-time motif which is referred to as a “the Sanctuary.”4 Because Scripture always presents God as acting and interacting within time, Adventism uses this principle, as opposed to a timeless view of God, to approach the narrative. The creation story, Sabbath day, theophanies, Old Testament sanctuary, which God instructed the Israelites to build so that he could “dwell among them,” incarnation of Christ, church, Holy Spirit, judgment process, and the New Jerusalem (located in earth, Rev. 21) all proclaim that God is not a distant, frozen, or aloof deity that cannot be impacted by the decisions of men but a present, intimate, and relational being who, while eternally sovereign, condescends to humanity. This presupposition is reflected in Adventism’s “Historicist” approach to Bible prophecy, in its concept of “present truth” (meaning God always has new truth to reveal which is why Advemtism is non-creedal), and in its views regarding the continuity of spiritual gifts (such as the gift of prophecy) which places God as active in the affairs of men throughout the entirety of human history which includes the post-canonical era.

The remaining presuppositions are all consequences of Adventism’s Sanctuary Narrative.

Christcentredness of Adventism

As mentioned in the last post, Adventism is a Christ-centred approach to Scripture’s story. According to Adventism, the Bible cannot be properly interpreted without Jesus as the beginning, center, and end of the entire account. The Sanctuary narrative makes this reality even more central, because it sees the centrality and activity of Jesus as part of the pre-creation covenant (Rev. 13:8), creation order (John 1:1-3), Old Testament (John 5:39), New Testament (Phil. 2:9), and eternity (Phil. 2:11).5 For Adventism, however, Christcentredness is not used as a way to avoid or discount other scriptural doctrines. While some Christian traditions use the centrality of Jesus as a means of devaluing other scriptural themes, Adventists use it as a means of strengthening every point of Scripture’s narrative. Christ at the center is the means by which we understand the other doctrines. Christ is the center and all other truths orbit around his person.

Adventism’s Anthro-peripheral Heremeneutic

(Anthro=man, peripheral=not central) One unfortunate outcome of all the diverse covenantal traditions we have explored is that, although they each deal with numerous issues, it is clear that what most people seemed to be concerned with is personal assurance of salvation and how the relationship between law and grace impacts them personally. For many, this is the most important and central element of covenantal thought. This is not the case for Adventism. Adventism holds not simply to a Christcentred presupposition but it also holds to an Anthro-peripheral presupposition which basically means that mankind’s salvation is not the main point of Scripture’s narrative. By using the Sanctuary narrative Adventism seeks to paint a gospel narrative that encompasses the entire narrative of redemption and not simply that which relates to human salvation. According to Adventism’s interpretation of the Sanctuary, the main point is the character of God which finds its fullest revelation in Jesus. Man’s salvation – especially the assurance of salvation – is certainly important and far from a fringe issue, but it remains second to the vindication of God’s character over against Satan’s lies about Him. Thus, while the law and personal salvation are important in Adventism, they are only small pieces of a much larger puzzle.

This is another reason why many Adventists simply don’t lose sleep over things like the law and the covenants. In many regards, the entire discussion can appear to be an over-complication because it places man and his salvation at such a central point in the story that even God himself has to step aside (abrogate his law) for them – a concept which, as already mentioned, is self-contradictory in an Adventist worldview. Thus, for Adventism, mankind is simply not what this is all about. The character of God is the issue. And while that character is revealed most fully in His salvation of man through Jesus’ sacrifice, the central point is nevertheless God’s character and not man’s salvation.6

We will pause here for the time being and allow these presuppositions to sink in before moving into an exploration on how they impact our understanding of the story of Scripture. In the next post that exploration will begin and will focus on the Big and Middle stories of Adventism.

Note: This article was originally published at www.pomopastor.com as “The Hole in Adventism: Identifying our Place in the Continuum of Protestant Covenantal Thought.” It has been edited for republication on Sabbath School Net.

[ Go Back to Read Part 4 | Go Forward to Read Part 6 ]

Footnotes:

- While it is true that Adventists place a lot of emphasis on prophecy – another aspect of the Little Story – it is important to note that prophecy, while a part of the Little Story, points clearly toward the return of Jesus, the end of the Great Controversy and the final restoration of all things. Thus it is a Little event that ever points toward the Middle and the Big Story. As a result, it plays a different role than the rest of the Little Story and consequently appeals to Adventist thought more. ↩

- Reid, George W. ““Another Look at Adventist Hermeneutics” ↩

- Davidson, Richard M. “Interpreting Scripture According to the Scriptures: Toward an Understanding of Seventh-day Adventist Hermeneutics” ↩

- Fortin, Denis. “Ellen G. White’s Conceptual Understanding of the Sanctuary and Hermeneutics.” ↩

- This is one of the reasons (apart from exegesis) why Adventists are not afraid to suggest that Michael the Archangel is an angelic, pre-incarnate manifestation of Jesus. While Adventism holds to the eternality of Jesus and his equality with the Father as an uncreated being, it does not find difficulty in the suggestion that just as Jesus condescended to mankind as a man, he had an angelic manifestation as well in the person of Michael. Of course, this concept plays no role in our theological development (as it does for Jehovah’s Witnesses for example who attempt to argue that Jesus is a created being) and is thus absent from our doctrinal formulation. It is nevertheless an often misunderstood by-product of the combination of our Christocentric/God-in-time pre-suppositions. ↩

- Sadly, this is a pre-supposition many Adventist’s lose sight of quite easily. The result is an obsession with topics like the Sabbath, health reform, or some other doctrinal point. Once the Anthro-peripheral presupposition is lost sight of, the entire narrative collapses and in its place emerges a doctrinal point which becomes the central feature of the person’s entire theology. However, by keeping the Anthro-peripheral perspective alive, the integrity of the Big Story is not lost and thus, doctrinal points remain in their proper sphere and relationship to the story as a whole as opposed to becoming the central feature. This tendency to forget the Anthro-peripheral perspective is at the root of why Adventists have historically been regarded as obsessed with the Sabbath, diet, or prophecy as opposed to what our narrative is truly all about: The character of God. For more information see also:

a) Timm, Alberto R. “Christ’s Ministry in the Heavenly Sanctuary: Recognizing Heavenly Realities“

b) Seventh-day Adventist Church Beliefs. “Salvation”

c) “Christ’s Ministry in the Heavenly Sanctuary“

d) “Did you Know that Jesus Christ is Our Judge and Advocate?” (video) ↩